Every cultural revolution has its home—a vital location which helps to shape and nurture new ideas. For mountain biking, there was Marin County, for skateboarding it was the empty swimming pools of California, and for rock-climbing as we know it today, there was Yosemite National Park.

But whilst some of these locations quickly fall out of favor, Yosemite has consistently maintained its position as the mecca of modern climbing—with each subsequent generation upping the ante and keeping the campfire fully blazing.

The late 1950s was ‘the Golden Age’—a time when climbers like Royal Robbins, Tom Frost and Yvon Chouinard revolutionized big wall climbing, making the first ascents of many of Yosemite’s most famous routes. Then there was the 70s—when the Stone Masters (including Gramicci founder Mike Graham) stripped things back, with a focus on speed and style.

By the late 90s a new generation had started to call Yosemite their home–a rag-tag, hard-to-define band of modern dirtbag climbers called the Stone Monkeys. Whereas the Stone Masters had pioneered the art of free climbing—a pure form of rock climbing where ropes and harnesses were only relied on in case of a fall—Stone Monkeys like Dean Potter, Steph Davis and Ammon McNeely took things one step further, climbing serious routes with no ropes at all.

Known as free soloing, this new form of climbing eschewed equipment in favor of absolute skill and technique–requiring not just serious physical strength but also the calm, methodical mind of a chess master.

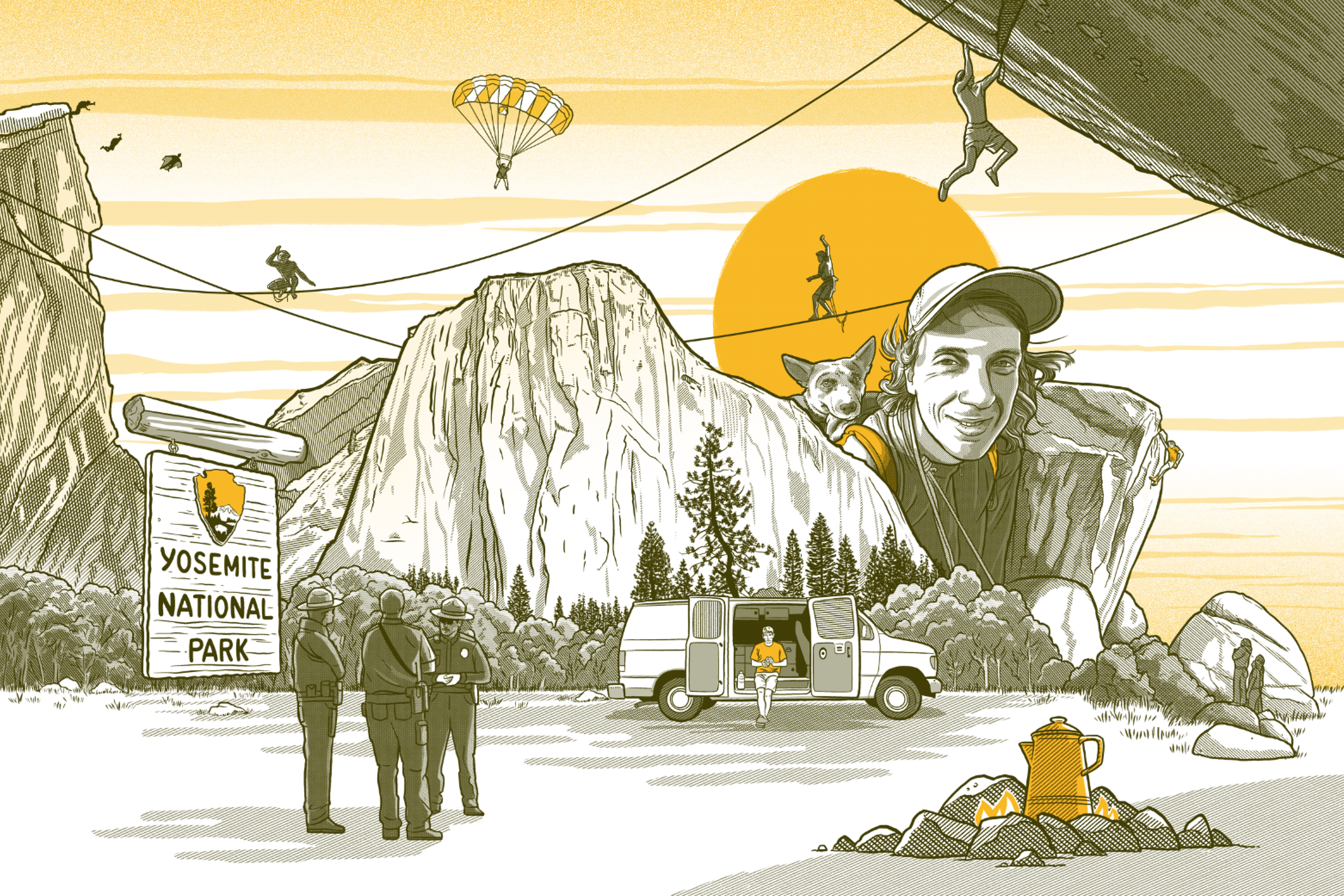

The minimal, pure way of climbing practiced by the Stone Monkeys was echoed in their way of life. By the 90s ‘the outdoors’ had become a huge industry, with bus-tours and bike parks cropping up allowing weekend warriors a safe taste of the great outdoors, yet the climbers of Yosemite lived an underground existence—sleeping in caves, dining out on free condiments nabbed from the cafeteria and endlessly running from the park rangers.

As the rules and regulations tightened around the USA’s National Parks, the counterculture dirt-bag lifestyle of the climbers of the Golden Age continued into the new millennium—the Stone Monkeys building on lessons learned by Yosemite legends like Dean Fidelman and Charles ‘Chongo’ Tucker III. There were no on-site physiotherapists or personal chefs for these rogue athletes, and their feats were accomplished in an off-grid manner, with the only ‘luxuries’ on offer a gas stove and a sleeping bag.

If anyone embodied the uncompromising Stone Monkeys ethos, it was probably Dean Potter. The 6’5” silverback of the tribe, known to some as the ‘Dark Wizard’ (thanks to his sometimes somber mood and his magical feats), Potter helped to introduce countless new methods of adrenaline release to the climbers of Yosemite, blurring boundaries between numerous extreme activities with a style he called ‘the art of no rules’.

Speed-climbing saw Potter and his cohorts practically running up routes and ‘highlining’ took slacklining—the humble act of walking across narrow nylon ribbons—into the heavens. Whilst slacklining was originally seen as a casual way to hone balance down on terra firma, the lines often tied between trees and pick-up trucks, people like Scott Balcom and Dean Potter pushed things thousands of feet up, sometimes without even a tether for support.

BASE jumping was another Stone Monkey favorite. By the late 90s specialist lightweight parachutes had been developed making the act of leaping off stationary objects easier than ever before—and the climbers of Yosemite soon got in on the action. From BASE jumping came ‘freebasing’’—a cunning combination of free soloing and BASE jumping where a lightweight parachute is used in case of a fall—and ‘baselining’—again using parachutes to take away the risk during highline balancing acts.

The addition of a parachute into the mix allowed climbers like Potter to try even wilder ropeless routes, feeling the freedom and purity of climbing without equipment getting in the way—whilst still offering a slight margin for error should things go wrong.

When BASE jumping became the norm (to a few people at least), webbed wingsuits were introduced, allowing controlled freefalls and perhaps the most dangerous ‘hobby’ ever devised—proximity flying—purposely gliding as close as possible to rock-faces and trees to accentuate the feeling of speed. Sadly these increasingly dangerous acts came at a price, and in 2015 Potter and his friend Graham Hunt tragically lost their lives in a wingsuit accident after jumping from Yosemite’s Taft Point.

With Potter’s death the Stone Monkeys era of Yosemite climbing was over, but a new generation—heavily inspired by their freeform style—was already waiting to take up the mantle. Two years later, when Alex Honnold climbed out of his Dodge van early one morning to scale the 3,000ft face of El Capitan with no ropes in sight, the influence of Dean Potter and the Stone Monkeys was undeniable. The ‘art of no rules’ lives on.